Director Justin Schein and Composer Bobby Johnston talk "DEATH & TAXES"

- Jul 16, 2025

- 15 min read

Interview from "On The Score" with Co-Director Justin Schein and Composer Bobby Johnston July 14 2025

By Dreldon

As they say, two things in life are certain, but how a documentarian’s dad gets there with bigger implications for everyone in America is a whole lot more welcoming and evocatively scored in “Death & Taxes.” As directed by Justin Schein (along with Robert Edwards) and scored by Bobby Johnston, an eclectic jazz-based soundtrack proves the key to family relationships often entirely determined by his father Harvey’s obsessiveness with avoiding the “death tax.” More properly known as the estate tax, it’s the final act of citizenship contrition where the government takes a bite of the departed’s financial belongings.

Given a hot topic from Democrat to Republican politicians for the respective give back and rob reasons, and a deeply personal one to Schein, “Death and Taxes” is the kind of documentary that takes what could be a talking head discourse and turns it into a profoundly moving film given the relationships at hand. But better yet, “Death & Taxes” grooves with Johnston’s scoring that ranges from Harvey’s old world Jewish origins to jazz that evolves from the birth of the cool to chart Harvey’s own hand in pop history and modern technology. Ironic, dreamlike and emotionally captivating, Johnston’s soundtrack (available on Movie Score Media) shows off the eclectic, eccentric talents of the composer whose music for the unreleased documentary “Extra” became a darling of NPR’s “This American Life.” His use of offbeat instruments, rhythm and melody has led to an eclectic career that’s accompanied such controversial filmmakers as Stuart Gordon (“King of the Ants,” “Edmond”) to Larry Clark (“Marfa Girl”) as well as covering the culinary canvas of Los Angeles for its tastemaker in “City of Gold.” First partnering with Schein on the documentary “No Impact Man” about a couple determined to live off the wasteful grid while being an inevitable urban part of it, Johnston and Schein’s synergy has never been more universally profound, or musically enervating as in “Death & Taxes,” turning what we all face (or try to run from) as citizens into a deeply affecting picture about far bigger truths.

Justin, what led you to documentaries?

JS: My first love growing up was photography, probably because I’m dyslexic, and the camera gave me a way to interact with the world and express myself unfettered by written language. I trace my interest in documentary back to my family’s Sunday night TV ritual. After dinner we’d all pile onto the bed for a night of classic 1970s non-fiction… “60 Minutes” followed by the “World at War” and (if I was allowed to stay up) “Mutual of Omaha’s Wild Kingdom.” In those three shows I got lost in the storytelling of documentary– journalism, history and nature.

Bobby, you’ve done numerous fictional films as well. But what do you think documentaries bring to your music, and do you enjoy scoring them just as much?

BJ: While I’ve scored far more fiction than documentary, my first couple of films (as well as my last couple) have been documentaries, which is kind of funny. Yes, I do enjoy scoring them as much as fiction, although they are different beasts. I think my music and the documentary genre tend to be a good match from a technical perspective, meaning that my music often has an “engine” to it, and with documentaries, many times you are accompanying information: talking heads, archival footage, graphics, charts, animation… so in contrast to closely accenting and supporting the emotional arcs of a fictional scene, documentary music is often required to be reinventing itself, to remain interesting without overselling it, and building toward a musically satisfying exit – without over editorializing, which I find to be much like live performance. Even though leitmotif isn’t used as much with documentary film scoring, you can still find threads and fabric to weave together thematic elements and form a musical identity which is unique to the film. When scoring the character arcs of the documentary subjects and the drama of the story, I find the process becomes very similar to scoring fiction films.

You both go back before “Death & Taxes.” How did your collaboration start, and how has it developed to the point of scoring this film? Do you both think of yourselves as unique in your artistic approach?

JS: Bobby composed the score for my first feature documentary “No Impact Man” – which I directed with his friend Laura Gabbert back in 2008. I really enjoyed his process. I remember sitting in his studio filled with instruments and found objects as he made strange sounds to the picture… We had a wonderful collaboration and the score was great.

BJ: I feel I benefitted greatly from getting to work with Justin and Laura at a relatively early part of my career. Justin and I also contributed to some of the same projects over the years, in different capacities, but “Death & Taxes” was the first chance that lined up for us to be able to work together again as director and composer, so I’m grateful for that. Also, Justin was in NYC during the scoring of “No Impact Man” while I was in LA. This was true for the scoring of “Death & Taxes” as well, so I guess you could say that we’re becoming proficient at long distance collaboration. I do feel my artistic approach to film scoring is unique and unconventional, in both my instrumental choices as well as in my execution – recording with live instruments rather than through sequencing and sampling, and also in playing most of the instruments myself – although sometimes, as in “Death & Taxes” I have the opportunity to bring in several soloists to accompany me.

Justin, what was your goal in making this? I love the moment where your wife urges this not be a film about “a poor little rich white boy story with the tiniest violin. This could have been a film solely about the estate tax, but it’s even more about the relationship between a son and father. What do you think that brings to the film and the score?

JS: For me the “goals” at the start of a project are about exploring questions. I don’t want to set out to prove a theory in a film. If I can show the complexity of an issue, make people question their preconceived ideas and start a conversation, then I feel like I have succeeded. A film just about the estate tax or a film just about my father would likely have been easier to make, but the challenge of interweaving the two felt much richer. Jazz is by its nature rich and complex with a full range of emotions… just like human relationships.

How did you decide on a musical approach for this? And why jazz in general? Were there any particular influences in that genre?

JS: My dad had built Columbia Records International in the 60s, traveling the world and acquiring local record companies to fold into CBS. He was all business and not involved with the artists, but he did love the music. Growing up he always had Billie Holiday, Ella Fitgerald, Miles Davis, Mingus records spinning… as he spent hours looking at the stock pages of the paper. As I got older and things were contentious between dad and me, there was a point in our relationship when I reached a crossroad. I was no longer rebellious teen and had to take some responsibility for the relationship. I decided to look for some common ground… and we found it in our mutual love of jazz. So, instead of arguing about politics we’d listen to jazz, talk about it, even go to concerts. And yes, we did argue about it a few times. We both loved Charles Mingus, and I took him to go see the Mingus Big Band at Time Café. Thus, when I started the film, I had jazz music in mind. As is too often the case – particularly on a production with a limited budget- a composer comes in towards the end of the process after a temp track has been used and the filmmakers are accustomed to it. On DNT this was made worse for Bobby because I had used a lot of Charles Mingus and other classic jazz. Replacing that was a tall order, but Bobby was undaunted… No matter how classic the temp cues are, music that is composed as a score, which is communicating with the images and themes and becomes a character in itself, is the best option.

What do you think a primarily jazz score brings to the film? And do you think it gives “Death & Taxes” a level of irony, especially when talking about taxes?

JS: A great influence for me is the work of filmmaker Alan Berliner. He is a master at telling personal stories with a wonderful collage of visual and aural styles. For me jazz, and Mingus in particular, has that quality… it can be playful, rich and complex … Additionally, there is a layer of the issues around race that comes into play in the history of taxes—and the disenfranchisement of blacks when it comes to the creation of wealth in America. Those issues are certainly present in the history of Jazz and in the way that artists – and particularly black artists, where treated in the music industry.

BJ: I think a jazz-based score allowed us to cover a number of time periods in the film, since jazz has such a rich and varied history. I also think it ties into the setting of NYC and reflects the energy, momentum and unpredictability of the city. It is also a genuine way that Justin and his father connected, so it has a personal meaning to the filmmaker, which I think comes through.

Justin, why did you decide on using animation to tell your stories in flashback. Bobby, what quality do you think that brought to the score?

JS: I had never used animation in a film before, but setting out to make a film about taxes felt daunting. I wanted it to be entertaining, visually interesting, even funny. So, I decided to consider all of the tools at my disposal. The idea of bringing the past to life in small, animated moments felt exciting… But (similar to my work with Bobby) I could not have make it work without the amazing talent of Roberto Biadi

BJ: First off, I think Roberto’s animation is so unique and vibrant, while still being somewhat minimal. I found inspiration in this and felt his animation was a good pairing with my musical approach. There aren’t many scenes I can think of that were strictly animation in the film – the clips were usually cut in with archival footage, news reel excerpts, interview clips – adding some levity and liveliness to the scenes, particularly when the topic was interpersonal (such as scenes highlighting tension between Justin and his father) or political (ex. tax policy – accenting what might otherwise be a bit of a “dry” subject). I think the expressiveness and the human feel of the animation gave me some inspiration to remain mindful of keeping those elements prominent in the score as well.

Bobby, how did you want to capture the immigrant / Jewish experience of Harvey? And how did you want the musical styles to reflect the passage of time and tastes?

BJ: Justin and I spoke of this aspect of Harvey’s story early on, and we found jazz to be a good medium for incorporating some elements (specifically, clarinets and strings) of Klezmer music, which was a suggestion of Justin’s – and happened to be right up my alley. A good example of illustrating the passage of time and musical tastes is the cue “Harvey at CBS”, which starts off with clarinets and piano to briefly highlight Harvey’s immigrant/Jewish experience, before hitting some big band inspired jazz elements to accompany the “glamorous” era of his rise at Columbia records, and then settling into a bouncy Rhodes electric piano comp section to underscore how the complexity of Harvey’s personality defined his later tenure in the record industry. That is an example within one cue, but some scenes required a nod to a specific era, such as the funk inspired piece “Two Extremes” which was scored for a scene about challenges NYC faced in the 1970s. I also felt my use of vintage/traditional instruments and live recording techniques throughout the score would reflect the time periods of the subjects’ stories.

Justin, given that this is such a deeply personal film, do you think that made the score even more important than if your family wasn’t in it, and it just dealt with taxes? Did this be centered on your family give you particular ideas for the music as well?

JS: You want your characters to have a unique musical theme which evolves as they evolve. Those themes are like their shadow of the subject… The sun has an arc across the sky, the film and its characters too should have an arc… Bobby is masterful at that.

What job do you think it is for a documentary score to “sell” the emotions you want people to feel, and the points you’re trying to make?

JS: I think the score can do some of the work… but if you are relying on the score to “sell” emotions, then you have a problem with the storytelling. As soon as a viewer feels the music is pushing you in an emotional direction, you are taken out of the story. The music can take your hand and lead you… but it can’t pull.

BJ: I feel it’s important for a documentary to not over-editorialize with the music, especially when the subject is political or societal. Justin did such a great job giving all sides of the tax debate a balanced voice in “Death & Taxes,” so I didn’t want to betray the careful work he had done there. When a documentary gets more into the characters’ stories and emotional arcs, I tend to lean into the music a little more. But I count on the director to help determine the right amount of emotive push and Justin had great notes and suggestions that helped strike the required tone for this film.

Bobby, how did you want to capture Harvey’s “character?” Given that he was one of the original “Hit Men,” how did you want to get across his background in the record business, let alone the role that Harvey played in the development of home media and audio?

BJ: For depicting Harvey’s professional accomplishments and his career in the recording business, we emphasized sophistication, precision, and glamour in the musical approach. As stated before, the Big Band influences, but also concentric horn lines, energetic drum fills… But the pieces also had to have some degree of calculation and control. A good example is the cue “Harvey at Sony”, which I intended to have a feeling of action and accomplishment to reflect his era as head of Sony America – at a time when the Walkman broke, heralding an exciting period of music media access in both directions between artists and consumers. So, I wanted the cue to have a bit of a celebratory aspect to it, but also a feeling of excitement and momentum.

How important was it go give Harvey a relatable depth of character, and humanity, in spite of his flaws?

JS: My dad’s complexity and his contradictions are what make him such a good subject…. Showing that was essential. As a filmmaker, even in “documentary”, you are constructing your characters, making choices and simplifying. The challenge when telling a story about someone you love is to do them justice while also make those decisions that need to tell a good story…

BJ: This consideration is really at the heart of Harvey’s musical themes in the film. The word we kept coming back to was “Complexity”, which is the title of a cue that was taken from the main title theme to later accent Harvey’s complicated and multi-faceted personality. He had the duality of someone with admirable and exceptional business accomplishments, who also put some intense pressure and expectations on his family members. Still, Justin openly talks about viewing his father as a superhero when he was a kid, which I think is something many people can relate to with regards to our relationships with our fathers. So, capturing Harvey’s depth of character and contradictions was certainly a priority with the music.

Contrastingly, how did you want to score his wife Joy, who, like her namesake is beyond patient, and much more of a humanitarian and creative artist? Tell us about your approach to their break-up

BJ: For Joy, I tried to give her musical themes a feeling of introspection, individuality and expression. I ended up settling on piano for her – particularly the upright because of its classic association with both dance studios and the traditional American home. An example of this was in using a vintage Baldwin upright on the scenes depicting Joy’s dancing career – and then using the same piano in a more modern context (but still minimally) when scoring the later scenes of her finding independence while struggling with her marriage to Harvey. When they became separated, we switched pianos to a vintage Steinway grand, with a version of the theme we used on the scenes of Harvey’s sickness and eventual passing, as it seemed akin to the scenes of their marriage coming apart.

Bobby, tell us about the instruments and players you put together for this. What were the scoring sessions like?

BJ: While I performed many of the instruments on the score, I was lucky to have several incredible musicians accompany me on this one too. Knowing we were going to do a jazz score, I brought in longtime horn players Dan Clucas (trumpet) and Brian Walsh (clarinets, saxophones), as well as cellist Ken Oak, and a pair of fantastic drummers who helped keep the “live” feel in the music – Joey Waronker and Chris Blondal. All this allowed me to create different jazz ensemble variations to give the score some depth and versatility. For the most part, sessions happened in my studio, but Joey recorded drum tracks for a couple of cues at his studio and my longtime co-orchestrator and composer of additional music William V. Malpede also recorded tracks at his studio – and he performed keyboards and piano on many of the cues. I was also lucky to have Marc Doten in to play piano on a couple of pieces, and I did quite a few of the piano parts myself, so I think that three-pronged approach gave us a lot of variety with the piano sounds.

The ending of the film is incredibly touching, especially when visually and musically summing up Harvey’s life and his thoughts on death. How did you come up with that structure and scoring approach?

JS: At the end of the film, as dad is truly facing his mortality, we see that his priorities have changed. He became wistful in his questioning what was next for him. Like our common love of jazz, dad and I both loved Coney Island, so I decided to use archival footage from the time of his youth to illustrate his retreat into memory… Bobby really took it on himself to interpret that musically and the results are beautiful

BJ: Funnily, this relates to what I was just saying about the piano approach, because it was central to how I scored this scene, which was a real challenge. For the opening section, where Harvey muses about life and death, I played some free form kind of chords and percussive piano rhythms on the old upright, which seemed to ground Harvey as he is coming to terms with his humanity and his mortality. Then when he passes and the scene shifts to a montage of his family and their memories, we switch to the pristine Steinway grand piano – where William V. Malpede plays more structured, dissonant chords that build into a crescendo and release – like only that type of piano can. So, this scene is a good example of the combining of pianos and pianists I did with some of the score cues.

Bobby, how did you personally relate to this film, even though it’s not your family. And do you think it’s important for a composer to relate to a subject, whether is fictional or real?

BJ: I could personally relate to the film because it’s such an honest depiction of family dynamics. Like many men, I had a complicated relationship with my own father, and, like Justin, I set out into a career in the arts at a young age. Justin and I are also of roughly the same age, so I could relate to the generational aspect of the story as well. As a response to the second part, I think it’s more important for a composer to “understand” a character or subject in a film than to relate to them – and as someone with a lot of credits in the horror genre, I don’t hope to relate to some of the characters I compose music for!, but in the case of a documentary film like “Death & Taxes,” I do think it was helpful to relate to the characters because it’s such a personal story.

Justin, what do you want people to come out of this documentary with, both in taxes and how they look at your family and father?

JS: The hope is that this film can be part of a shift in the conversation about taxes. Taxes are a choice we make as a society (assuming we are still a democracy) which reflects our priorities and our morality. There are winners and losers, and for too long the wealthy have been putting their (our) finger on the scale so that we can avoid paying our fair share. We are such a rich country… there is no reason for the majority of people to be insecure (on the edge of poverty) while a tiny fraction have so much. The solution is not all or nothing, there is plenty of room for compromise. Closing some of loopholes that make it so easy to avoid paying estate taxes is a clear first step. As Matthew Desmond, the sociologist, says in the film, “If the wealthy just paid what they owed, not more- then we could just about wipe out poverty in America.” As for my dad, I needed to show his motivations were complex and at their heart unselfish… That his mishigas around money and taxes were a complex reaction to his childhood that both served him (in the corporate world) and hunted him in his personal life. My hope is that this gets beyond the stereotype of the wealthy businessman and shows his humanity. And lastly- at this moment when we are so divided as a country… where families can no longer come together for holidays, my hope is that “Death & Taxes” shows that two people – a father and son- can disagree but still love and respect one another.

What’s up ahead for you both? And are your estates planned?

JS: “Death & Taxes” is beginning its theatrical release in NYC on the 17th at the IFC then moving west. At this moment when the budget and tax cuts are being debated in DC, that is my fulltime focus. As for my estate… My dad would likely be both appalled at how little time I have spent strategizing and taking full advantage of tax loopholes… and part of him would be pleased that I am not as obsessed about it as he was.

BJ: We have a soundtrack event coming up around the film’s LA premiere, and I am also doing a good bit of live performance in the Los Angeles area with my band The Open Orbit Orchestra these days. I am also currently working on a couple of writing projects, which is a passion I try to balance with music. Yes, my estate is planned, but not to an obsessive degree.

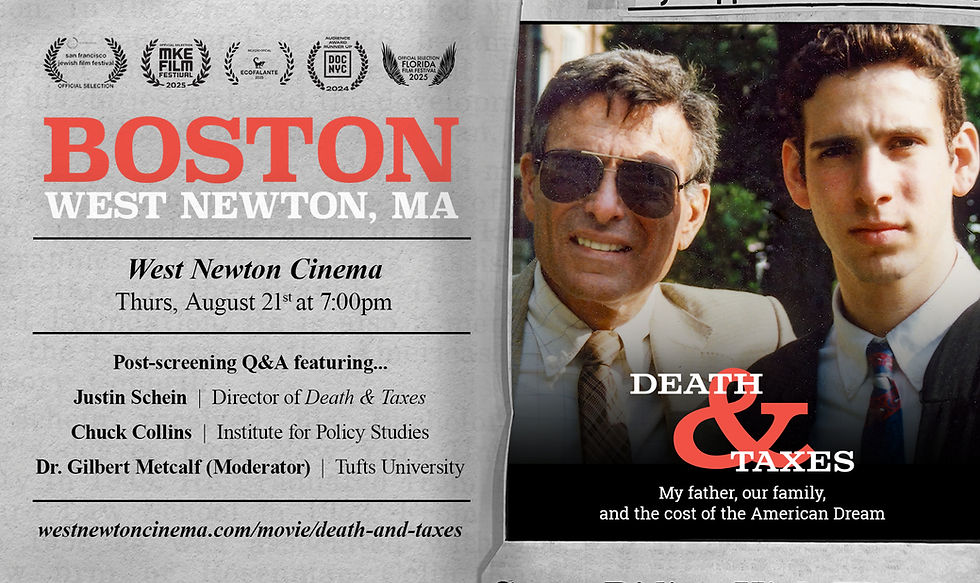

“Death & Taxes” opens in New York City on July 17th at The IFC Center and July 25th at The Laemmle Royal in Los Angles for a week-long run in each city. Meet Bobby Johnston for a special music screening event July 27 at the Royal. Visit the film’s web site HERE for more information. Buy Bobby Johnson’s soundtrack on Movie Score Media HERE and visit his website HERE. Visit Justin Schein’s website HERE

Special thanks to Sasha Berman

Comments